Myst (1993) is a classic and at this time still one of the most historically relevant computer games. Its impact on the industry is absolutely relevant as the killer app that cemented CD-ROM and Windows as standards, while in terms of game design it delivered the final blow that relegated text adventures to the realm of the dedicated indie set. Despite this it ended up taking the mantle of the thinking man’s game, especially considering that 1993 saw the release of another of computer game’s milestones: DOOM. Myst sold the computer, but after getting utterly confused after the first few areas, everyone put it back in the box and booted up a pirated floppy of DOOM. I personally didn’t grow up on Myst although I recall trying realMyst and I’ve played a quite few of its clones over the years. Of these, the ones I most fondly remember are The Neverhood (1996) which for years was a true favourite, The Last Express (1997) which is another favourite although played much later, Ring (1998), Return to Mysterious Island (2004) and certainly a few other, mainly European early XXI century ones, whose names now escape me. I would consider The Return of the Obra Dinn, a top favourite, something else entirely that happens to share some of the same game mechanics.

Much like text adventures, Myst and its clones usually provide their most memorable moments right at the beginning, where the average player will progress to. Progress was usually slow, puzzles doted with hard to grasp logic which were usually incoherent with the logic set of the game world ("why would an alien race hide a teleport device behind a checkers puzzle?").

I had tried Obduction once before but hadn’t given it a proper go as I invariably got distracted with something else. The Riven remake that came out this year caught my eye and I thought now was the time to get into this. As for first impressions it’s hard to believe this game is going to be 9 years old this year because it looks incredible. The game was co-developed as a VR game and some measure of this is palpable in the way you interact with the world. I don’t have a VR set but I can say that this would be a game that I would really like to see in VR and the fact that it was made with VR in mind in no way detracts from playing it without VR. Movement is either free-flowing or scene by scene as in the old games – I opted to play free-flowing.

There are a couple of design choices that are worth addressing in a positive light. One is the use of FMV. You know in FMV you rarely get outstanding acting but it adds to the quirk of the game and it looks fine in the otherwise photorealistic environments, much more so than animated polygons would. Since these scenes are quite few it does add to the charm and nostalgia. Another point is the complete lack of an inventory. What this means is that every puzzle will be solvable by what is there: buttons, doors, pulleys, teleporters, you name it. This lack of objects also means there is no map, which as the gameworld gathers complexity may or may not become a problem. This is a bit of a nod as well to the old. It’s almost mandatory to take notes (digital or otherwise) to beat the game.

As far as the important first impressions go it is rightly impressive how perfectly the challenges are laid. Right from the start you see doors you can’t open yet, rivers that are yet uncrossable and machines you can’t operate. But, little by little, the challenges keep coming and you start taking down, one by one, all the barriers put in front of you. What is immediately surprising is that right up until the end, while challenging there is none of the abstract “puzzling for the sake of being puzzling” designs here. Everything makes sense and as long as you’re thorough, a good observant and make notes everything is surmountable. This is a delight as you make progress relatively quickly and being stuck is usually just a case of perhaps something which was forgotten, overlooked or un-noted. Above all, everything makes sense.

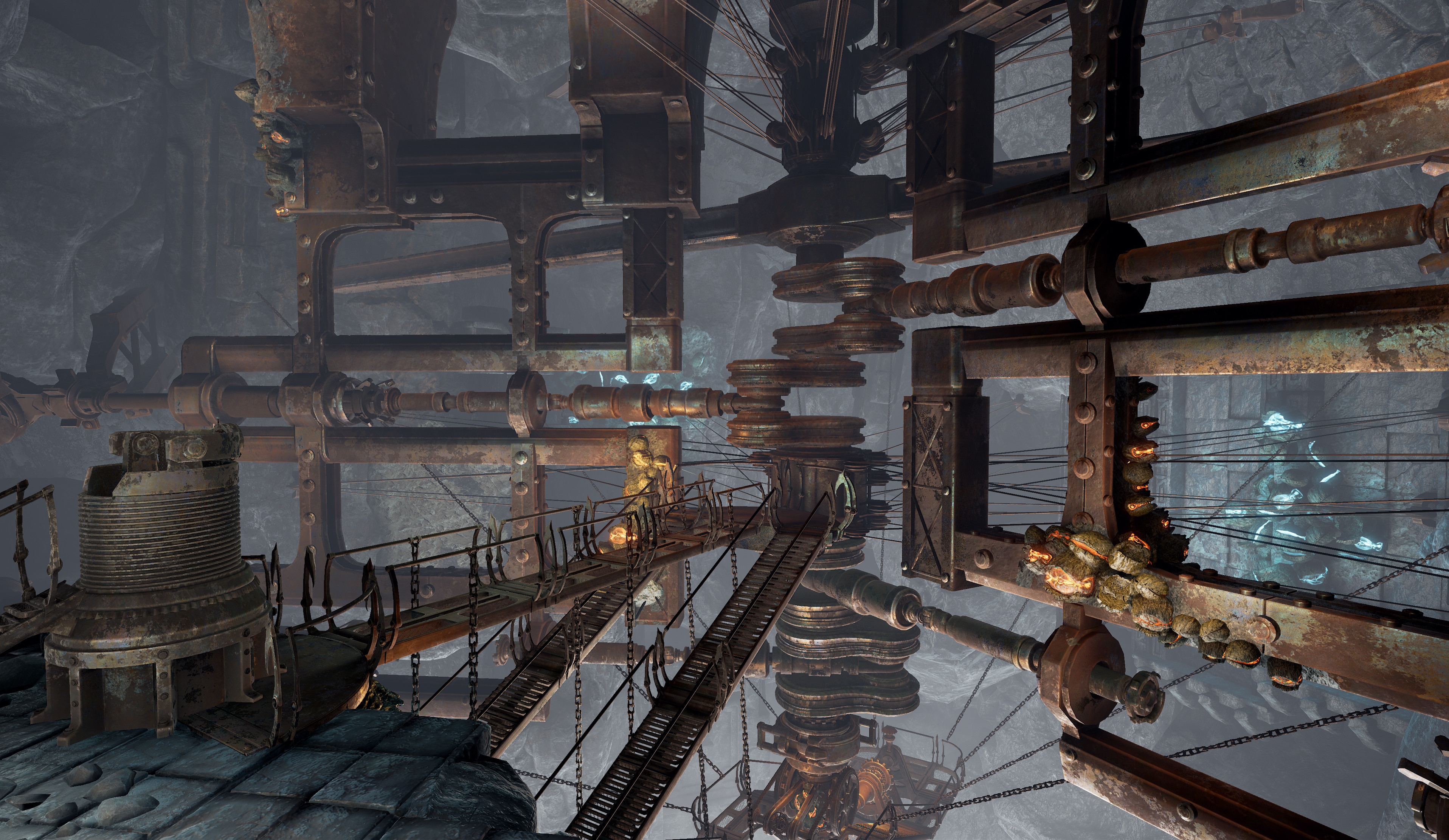

The gameworld is the ultimate puzzle, the one every small puzzle contributes to. Apart from making it technically so satisfying to uncover and beautiful to see, the fact is that there is also artistic merit in the way it is designed, unifying western and s-f sensibilities with a touch of the steampunk added in. The lack of a map forces you to build a mental map of the long-game puzzle which happens to be the game world itself. Unfortunately, the last quarter or fifth of the game, without spoiling anything hopefully, becomes quite a lot more convoluted and inane and, quite frankly, just laborious and artificially annoying puzzles surface (what I mean by this: for instance having to physically travel between far away locations to move different pieces on the same puzzle).

While movement is relatively zippy thanks to the WASD+Shift controls, the fact is by end-game you’re moving all over the map because certain areas are only accessible through other specific areas. Some sort of instant travel would have made it rather less painful although, in a way, contrary to its heritage.

Also unlike most other games of the same type the story is especially captivating. While later on it gets understandably convoluted, there is an intrigue here as you peel back the layers and start to understand what is really going on. The fact that this is done all by exploring the game world made it a lot more endearing. In a game with few characters and where everything, to some extent, has already happened, I have to consider this fact quite worthy of merit.

What to make of Obduction then? For me this was the most technically enjoyable first-person, Myst-like adventure I’ve played. Of course, The Neverhood and The Last Express are gems just by being what they are, although its technical issues stopped them from living up to the expectations they set. On the other hand Obduction actually moves the now dilapidated genre forward. It’s interesting that it came out in the same year as The Witness, which was far more celebrated then. Still, I would consider this one the better game, even if conceptually not as refreshing. Its real inventiveness lies in the way Cyan presents the gameworld. It’s a closed structure that you’re gradually uncovering in a flawless rhythm. It’s a shame that that rhythm comes to a syncopated, irregular and sweaty ending. Running out of steam? A nod to their heritage and the fans from back then? The result of being a Kickstarter-funded game?

All things considered, and in a way, I would argue that these sort of games, much like their polar opposites arcade games, aren’t as much meant to be beaten but to be enjoyed, within your own limits, for as long as possible. In that sense, the way it sets a perfect pacing of the puzzles and opening up the gameworld like a flower at the start is done in a way which I hadn’t really experienced before. Its last leg is perhaps thought of as a punishing boss – something cruel and laborious where only masochists will persevere.

Although I suspect the Myst and Riven remakes, adapted as they are for modern sensibilities will not change their core content and should still be filled with puzzling inanity. However, I have certainly renewed my interest in Firmament (2023), which seems to have gone under the radar. While Obduction's last impressions weren’t as enchanting as the first, I have no doubt I will want to replay this, to soak in its atmosphere and relive the enjoyment of reconnecting all of this wonderful game world again.

No comments:

Post a Comment